““A person can suffer as a child and still build a life of love and social activism.””

I was born in Berlin and grew up as a Jewish child in Nazi-occupied Europe. A survivor of two concentration camps I came to the US in 1945. Since the late 80’s I have been teaching students about the Holocaust and the lessons I learned during those traumatic years. My memoir, Shores Beyond Shores, details my journey.

I'm a co-founder of the Raoul Wallenberg Medal & Lecture series at the University of Michigan, and one of the founders of Zeitouna, an Arab/Jewish Women's Dialogue group in Ann Arbor.

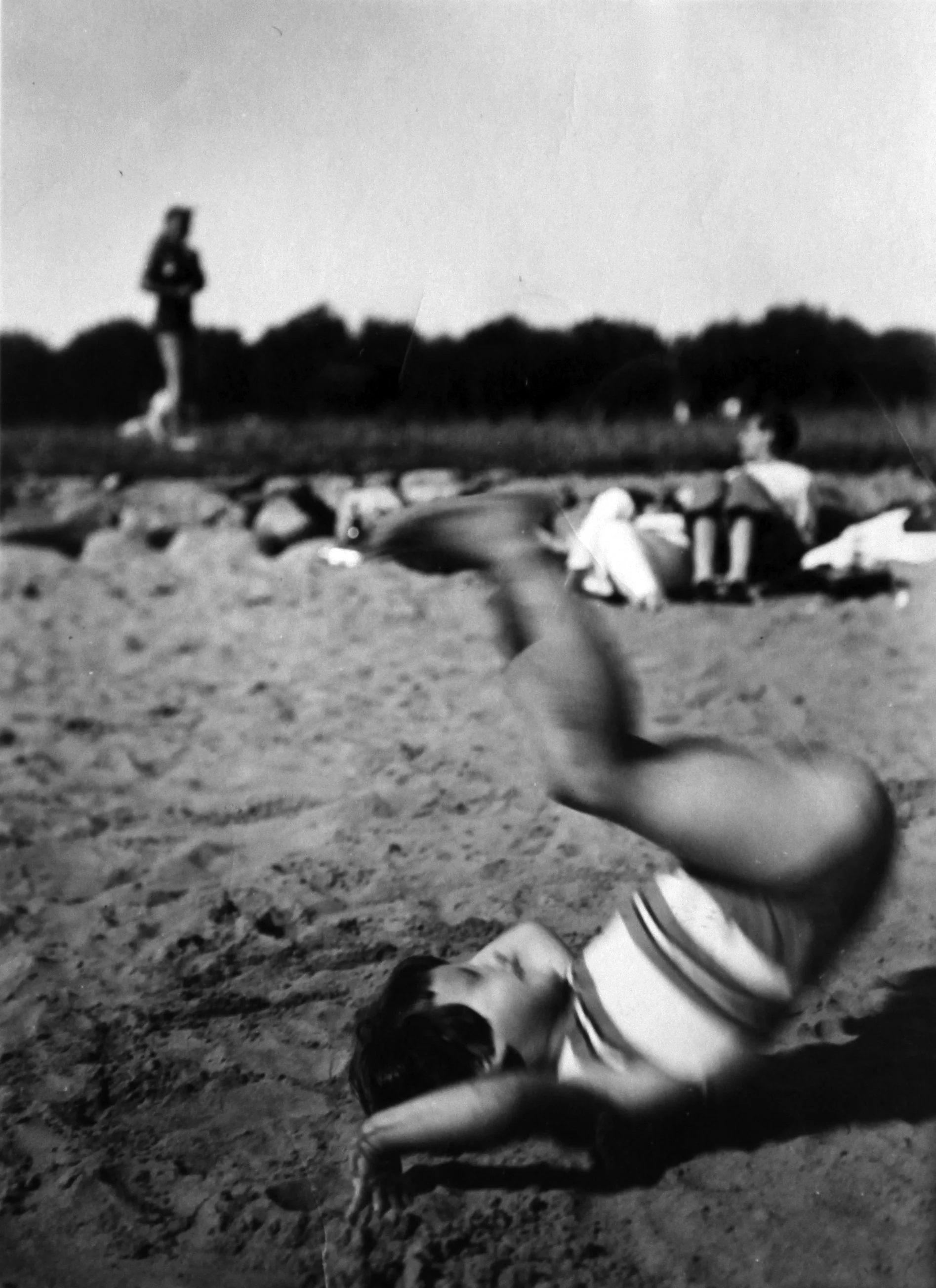

Here I am doing a somersault on the beach, circa 1935

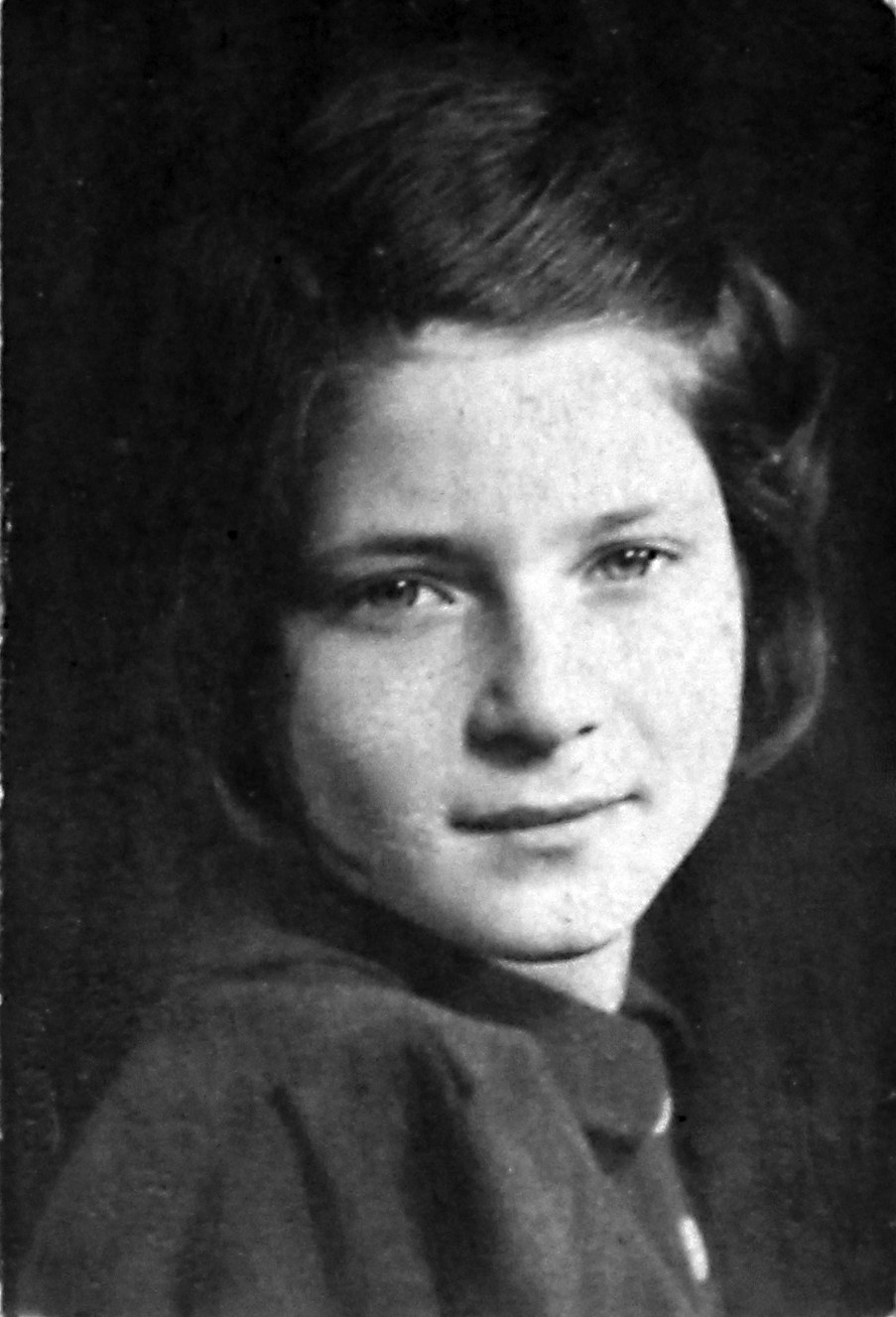

I'm in second grade at Vondelschool in Amsterdam in 1938

Her father's entry in Irene's memories book, or Poesie, from June 8, 1940: "My little love, you are mine, you belong to me, you are the dearest. Your father."

Irene’s Star of David she had to wear at all times in Amsterdam to identify her as a Jew. It was stolen from Irene’s home in the early 2000s.

A copy of the passport photo used for my Ecuadorian passport, circa 1942

I gained back weight, and then some, in the refugee Camp Jeanne d'Arc in Algeria, 1945

As a university student in the 50's

Germany

I was born Irene Hasenberg in 1930 and lived in Berlin for the first six and a half years of my life with my Pappi (John), Mutti (Gertrude), and brother Werner. Most people called me Reni.

My childhood in Germany was wonderful. I spent most of my time with friends and family, including my loving grandparents. We worked in their garden, visited the zoo, and shopped. I was spoiled, and unaware of the political upheaval around me.

Things really started to change when the Nazis took away the family business–a bank–and gave it to non-Jews. Feeling that things would only get worse my Pappi looked for work outside the country. This was a hard decision and not just because of the business. My family had lived in Germany for generations. My father had fought for Germany during the First World War.

The Netherlands

My Pappi found a new job with American Express in Amsterdam. Feeling this was far enough from the growing Nazi threat, he moved us there in 1937. We were not alone. Other Jews fled Germany, like Anne Frank and her family who moved to the same Amsterdam neighborhood. Anne was two years older than me, but we had mutual friends and I knew enough of her to look up to her.

Our first few years in the Netherlands were comfortable, but we had not moved far enough. In 1940 Germany invaded and once again we were under Nazi oppression.

As Jews, our rights were continuously restricted, and we heard of Jews being rounded up and sent to camps. Of course, this was happening wherever the Nazis were in control. My grandparents, still in Germany, were taken away to Theresianstadt concentration camp in 1942 and we never saw them again.

In winter 1943 we were rounded up and held at the Jewish Theater in Amsterdam. My father's connections saved us, and we were some of the few to be allowed to go home. My Pappi doubled his efforts to save us, including getting in touch with a Swedish man about Ecuadorian passports.

Camp Westerbork

Before we could get the passports, we were rounded up again on June 20, 1943 and sent to Westerbork transit camp, a stopover for Dutch Jews before being sent to extermination camps.

While Westerbork was not an extermination camp, it was terrifying, especially every Monday night when the names of those being sent to extermination camps would be read aloud. The goal was to stay off those trains, and again Pappi's connections helped. At the same time a surprise package arrived: our Ecuadorian passports.

The passports didn't allow us freedom, but they did give us a different status. Officials knew the passports were not valid, but the Germans needed prisoners to trade for German prisoners held by the Allies. Pappi said the passports might keep us alive.

Camp Bergen-Belsen

We managed to stay in Westerbork longer than most, but eventually we were put on a train in February 1944 for Bergen-Belsen, which was a far worse place. We were greeted by snarling dogs and brutal guards. The lack of food, overcrowding, slave labor, and poor health conditions took their toll. My family got sick and couldn't get better, especially Mutti.

Anne Frank

By January 1945 things were bleak. Mutti was confined to bed, Pappi was very weak, and Werner had a serious foot infection. My best friend in the camp was Hanneli Goslar, who was also from Amsterdam. One day she was shocked to learn that her best friend from Amsterdam, Anne Frank, was in Bergen-Belsen. Anne was in neighboring section of the camp, but we could meet with her at the barbed wire fence. Anne and her sister were very sick so we offered to collect what clothing we could and throw it over to her. We did, but before Anne could get it another woman stole the package.

Freedom

We told Anne that we would return the next night, but that wasn't to be for me. The Germans announced that my family was to finally be exchanged, and was to board a train the next day. We came close to not making it. Mutti was so sick that we were almost kept back, but then a miracle: I was confused for Mutti and we were declared healthy enough to depart.

But freedom came at a horrible cost. Pappi was beaten soon before we left, and two days out of Bergen-Belsen he died. His body was left at the train station in Biberach, Germany.

Alone

In Switzerland, Mutti and Werner were rushed to the hospital, and I was declared healthy enough to keep going. Against my wishes, I was put on a train for Marseilles and then a ship for Algeria. The Swiss did what even the Nazis never did: they tore apart my family.

Algeria

We were sent to a refugee camp, Camp Jeanne d'Arc, where we ate, healed, and absorbed the warmth of the sun, but I was depressed, suffering from the death of my Pappi and uncertain as to the health of my Mutti and brother.

Slowly I healed and opened my heart. I finally received word that Mutti and Werner would live. I gained weight, discovered swimming, and made new friends, including a love, Lex.

With the war's end, displaced persons, including Lex, made their way home and I was one of handful refugees left in north Africa. In the late fall I boarded an American Liberty ship and sailed for the United States, arriving in Baltimore harbor on Christmas Eve, 1945. Mutti and Werner flew to the States and we were reunited six months later.

The states

Upon arrival, I was told not to talk about my experience so I focused on high school, graduating from Queens College in New York City, and becoming one of the first women to earn a Ph.D. in economics from Duke University.

I met another student, Charlie Butter, and fell in love. We married, had two children, and became professors at the University of Michigan. Through most of those decades I didn't talk about my experience.

When my daughter Pamela was in high school she said she was doing a project on the Holocaust. Would I share my story? I did with her class. Then a few years later I was invited to participate on a panel about Anne Frank. Since Anne was no longer with us to share her story, I realized the importance of my responsibility in speaking of what we had endured. With a larger and more public audience, I fully found my voice. I started visiting more and more schools and was moved by how much the audiences, especially students, appreciated my story. I pursued peace work, cofounding the University of Michigan Wallenberg lectures and Zeituna, an Arab-Jewish women's dialog group.

I didn't ask to go through the Holocaust, but I was saved through the miracles of luck and the love and determination of my Pappi. I owe it to him and everybody who suffered to talk about what I learned because suffering never ends, so our work must continue.